Forgotten dates & wrong birthdays

Pre India's independence many families didn't record their children's date of birth.

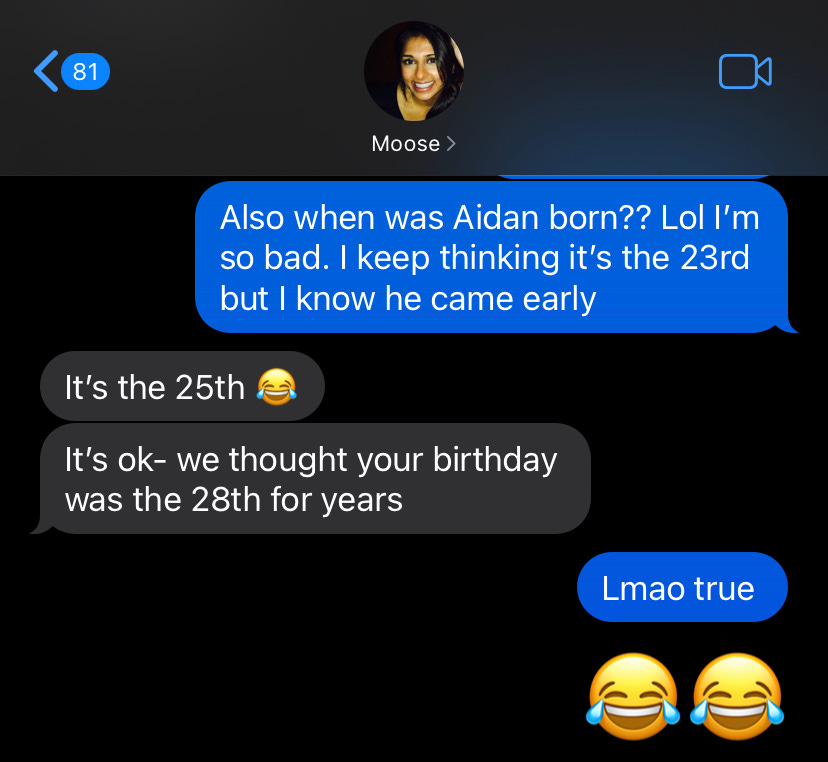

For the first 12ish years of my life, I celebrated my birthday on July 28th. In 8th grade, my friend Alex Stoprya wrote an essay for our English class titled “the girl who never knew her birthday”.

One random summer day of my pre-teen existence, my mom was going through the cabinets underneath the dark wooden dresser in my parent’s room of our old house. She found my birth certificate and that was the day I learned my birthday was on July 27th. It was also the day I realized I’d been incorrectly filling out most of my school papers. To be fair, I had only been celebrating a day off but it’s weird to go through life thinking one date was the day you were born and the next day be like “oh okay now I’m a July 27th baby”. On the bright side, it didn’t change my Zodiac sign. Thank god. I always have and will be a Leo at heart.

I share this story because birthdays in my family weren’t really significant and it was because for generations in my family, the exact dates weren’t a big deal to know.

My mother’s date of birth is unknown although we are sure she was born in 1958. In India, birth certificates weren’t created for babies until after the panchayat, or central governance of the village was created. This occurred post India’s independence in 1947, but even then, many families didn’t begin recording their children’s date of birth because they didn’t feel it was important, it wasn’t a common practice, or both. For the children who didn’t have recorded birth dates, our village created false dates when paperwork was needed. Many members of my extended family were part of that, including my mother.

Rather than dates, seasons were at the epicenter of the community. Traditions, rituals, festivals, births, and marriages were based on the time of year and moon cycles. Nature dictated daily life.

The community was dependent on farming for survival, so village life revolved around the seasons. My dad remembers Harotra, one of the most important religious and cultural traditions that was practiced by farmers at the time. It took place after the Indian New Year and during the first rain of Asad, the time of year that falls in the month of August. Harotra was a prayer ritual in which the entire village came together on the farm land to worship and pray to the land and the tools that were to be used for that season. As a child, my dad remembers the decorated oxen and the chanlo, the symbolic red dot made of Kumkum (dried turmeric powder) that was placed on the oxen. The prayer was done with the laborer and the laborer would go on to do the same to the tools. Harotra marked the beginning of a new year and a new farming season.

Harotra was seen as an offering to the earth. There was no fancy word or reason as to why they did this. It is what made the most sense because it was the community and the earth which they depended upon. They needed each other.

The practice of Harotra was widely practiced when my father was a child, but by the time he left the villages to come to the U.S. in the 80’s, it was no longer practiced. After villagers began migrating to cities for work and mechanized forms of farming were introduced, villagers forgot it was so central to farming practices.

Prior to seed commercialization and tractors, vegetables always grew in seasons, thus making each dish cooked for the family unique for that season.

On my visits back to India, the uniform fields stood in stark contrast to the vegetables that were once grown without chemicals and pesticides. Today, seeds are bought from a major supplier which come from the few big agricultural companies. Before the 70’s, my mother recalled using seeds from the previous season’s crops. She told me that if a neighbor needed to grow a certain vegetable and they didn’t have that seed, they often exchanged with a neighbor or someone else in the village. These seeds that were exchanged were the very seeds that our ancestors had experimented with for thousands of years. These indigenous seeds were kept season after season and it was customary to trade as needed.

The vegetables and grains that were grown were kept for the home, and then sold to other villagers. Crops were commonly used in the village community and then traded or sold to other villagers.

The relationship between the natural world and daily social life was once symbiotic. The seasons symbolized the rhythms of life, an eternal cycle encapsulating births, deaths, and everything in between.

I find that amazing that birth dates weren't important but understandable with life over there years ago being hard. Good read as usual!